The statistically improbable phrases that Amazon generates from a book’s contents seem like they’d be useful to have for a lot of other text content, such as emails or web pages. In particular, it seems like you could do some crude but useful automatic tagging.

There’s no technical information available on the algorithm they use, just a vague description of the results it’s trying to achieve. They define a SIP as "a phrase that occurs a large

number of times in a particular book relative to all Search Inside!

books".

The obvious implementation of this for a word or series of words in a candidate text is

- Calculate how frequently the word or phrase occurs in the current text, by dividing the number of occurrences by the total number of words in the text. Call this Candidate Frequency.

- Calculate the frequency of the same word of phrase in a larger reference set of set, to get the average frequency that you’d expect it to appear in a typical text. Call this Usual Frequency.

- To get the Unusualness Score for how unusual a word or phrase is, divide the Candidate Frequency by the Usual Frequency.

In practical terms, if a word appears often in the candidate text, but appears rarely in the reference texts, it will have a high value for Candidate Frequency and a low Usual Frequency, giving a high overall Unusualness Score.

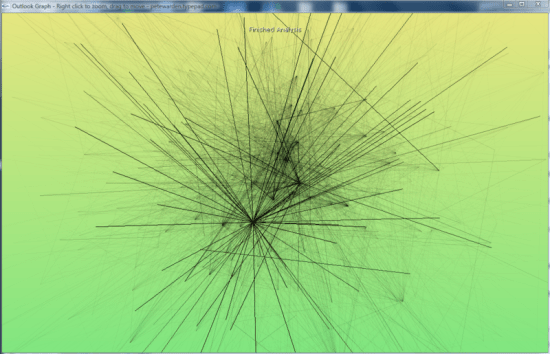

This isn’t too hard to implement, so I’ve been experimenting using Outlook Graph. I take my entire collection of emails as a reference corpus, and then for every sender I apply this algorithm to the text of their emails to obtain the top-scoring improbable phrases. Interestingly, the results aren’t as compelling as Amazon’s. A lot of words that intuitively aren’t very helpful showing up near the top.

I have found a few discussions online from people who’ve attempted something similar. Most useful were Mark Liberman’s intial thoughts on how we pick out key phrases, where he discusses using "simple ratios of observed frequencies to general expectations", and how they will fail because "such tests will pick out far too many words and phrases whose expected frequency over the span of text in question is nearly zero". This sounds like a plausible explanation for some of the quality of the results I’m seeing.

In a later post, he analyzes Amazon’s SIP results, to try and understand what it’s doing under the hood. The key thing he seems to uncover is that "Amazon is limiting SIPs to things that are plausibly phrases in a linguistic sense". In other words, they’re not just applying a simplistic statistical model to pick out SIPs, they’re doing some other sorting to determine what combinations of words are acceptable as likely phrases. I’m trying to avoid that sort of linguistic analysis, since once you get into trying to understand the meaning of a text in any way, you’re suddenly looking at a mountain of hairy unsolved AI problems, and at the very least a lot of engineering effort.

As a counter-example, S Anand applied the same approach I’m using to Calvin and Hobbes, and got respectable-looking results for both single words and phrases, though he too believes that "clearly Amazon’s gotten much further with their system".

There are some other explanations for the quality of the results I’m getting so far. Email is a very informal and unstructured medium compared to books. There’s a lot more bumpf, stuff like header information that creeps into the main text that isn’t intended for humans to understand. Emails can also be a lot less focused on describing a particular subject or set of concepts, a lot closer to natural speech with content-free filler such as ‘hello’ and ‘with regards’. It’s possible too that trying to pull out keywords from all of a particular person’s sent emails is not a solvable problem, that there’s too much variance in what any one person discusses.

One tweak I found that really improved the quality was discarding any word that only occurs once in the candidate text. That seems to remove some of the noise of junk words, since the repetition of a token usually means it’s a genuine word and not just some random characters that have crept in.

Another possible source of error is the reference text I’m comparing against. Using all emails has a certain elegance, since it’s both easily available in this context, and will give personalized results for every user, based on what’s usual in their world. As an alternative, whilst looking at a paper on Automatically Discovering Word Senses, I came across the MiniPAR project, which includes a word frequency list generated from AP news stories. It will be interesting to try both this and the large Google corpus as the reference instead, and see what difference that makes.

I’m having a lot of fun trying to wrestle this into a usable tool, it feels very promising, and surprisingly neglected. One way of looking at what I’m trying to do is as the inverse of the search problem. Instead of asking ‘Which documents match the terms I’m searching for?’, I’m trying to answer ‘Which terms would find the document I’m looking at in a search?’. This brings up a lot of interesting avenues with search in general, such as suggesting other searches you might try based on the contents of results that seem related to what you’re after. Right now though, it feels like I’m not too far from having something useful for tagging emails.

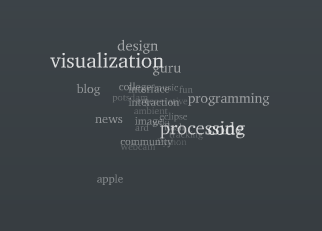

As a final note, here’s an example of the top single-word results I’m getting for an old trailworking friend of mine:

The anti-immigration one is surprising, I don’t remember that ever coming up, but the others are mostly places or objects that have some relevance to our emails.

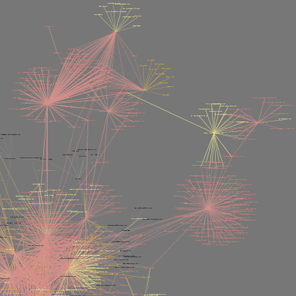

One thing I always find incredibly useful, and the reason I created Outlook Graph in the first place, is transforming large data sets into something you can see. For the SIPs problem, the input variables we’ve got to play with are the candidate and reference frequencies of words. Essentially, I’m trying to find a pattern I can exploit, some correlation between how interesting a word is and the values it has for those two. The best way of spotting those sort of correlations is to draw your data as a 2D scatter graph and see what emerges. In this case, I’m plotting all of the words from a senders emails over the main graph, with the horizontal axis the frequency in the current emails, and the vertical axis representing how often a word shows up in all emails.

You can see there’s a big log jam of words in the bottom left that are rare in both the candidate text, and the background. Towards the top-right corner are the words that are frequent in both, like ‘this’. The interesting ones are towards the bottom right, which represents words frequent in the current text, but infrequent in the reference. These are things like ‘trails’, ‘work’ or ‘drive’ that are distinctive to this person’s emails.