Matthew Hurst, from Microsoft, gave the second Defrag talk on the topic of visualizing social media. He described JC Herz’s first talk as complementary to his, covering some of the same problems, but from a different angle. He started by laying out his basic thesis. Visualization is so useful because it’s a powerful way to present context to individual data points. It ties into the theme of the conference because while web 1.0 was a very linear experience, flicking through pages in some order, 2.0 is far more non-linear, and visualizations can help people understand the data they now have to deal with through placing it in a rich context.

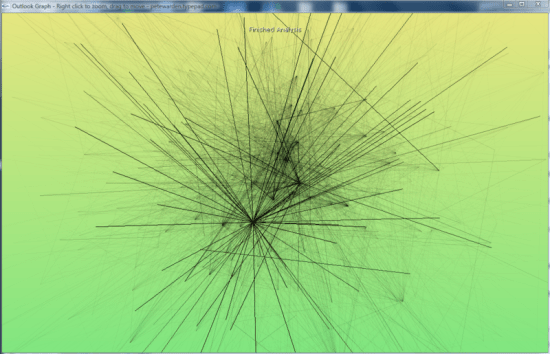

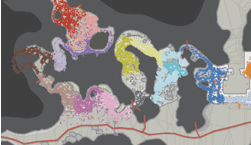

He then ran through a series of examples, starting with the same blog map that he’d created, and JC had used as a negative example in her talk. He explained the context and significance of the images, as well as the fact they were stills from a dynamic system, but did agree that in general these network visualizations have too much data. He introduced a small ‘Homer’ icon that he added to any example that produced an ‘mmmm, shiny, pretty pictures’ reaction in most people, without necessarily communicating any useful information.

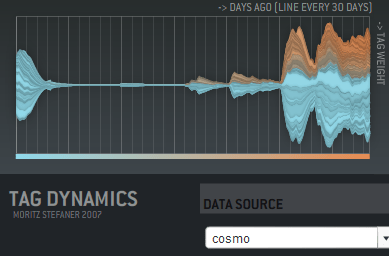

The next example was a graph of the blogosphere traffic on the Gonzales story, generated by BuzzMetrics. This was a good demonstration of how useful time can be in a visualization. After that came an impressive interlocked graph, which after giving the audience a few seconds to oh and ah over, he introduced as a piece of 70’s string art! A pure Homer-pleaser, with no information content.

The next picture was a visualization of the changes in Wikipedia’s evolution article over time. This was really useful image, because you could see structures and patterns emerge in the editing that would be tough to see any other way. There’d been an edit war over the definition of evolution, and the picture made it clear exactly how the battle had been waged.

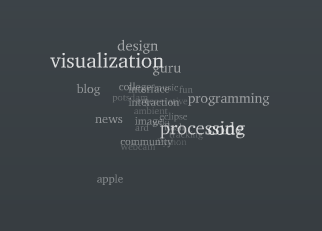

TwitterVision got a lot of attention, but isn’t much use for anything. It gives you information in a fun and compelling way, but unfortunately it’s not information that will lead you to take any action. To sum up the point of showing these visualizations, he wanted to get across that there’s a lot of techniques beyond network graphs.

He moved on to answering the question "What is visualization?". His reply is that the goal of visualization is insight, not graphics. Visualizations should answer questions we didn’t know we had. He returned to the blogosphere map example, to defend it in more detail. He explained how once you knew the context, the placement and linkages between the technology and political parts of the blogosphere were revealed as very important and influential, and how the density of the political blogosphere revealed the passion and importance of blogs on politics.

(Incidentally, this discussion about whether a visualization makes sense at first glance reminds me of the parallel endless arguments about whether a user interface is intuitive. A designer quote I’ve had beaten into me is ‘All interfaces are learnt, even the nipple’. The same goes for visualization, there always has to be some labelling, explanation, familiarity with the metaphors used and understanding of the real-world situation it represents to make sense of a picture. Maps are a visualization we all take for granted as immediately obvious, but basing maps on absolute measurements rather than travel time or symbolic and relative importance isn’t something most cultures in history would immediately understand.)

He also talked about some to Tufte’s principles, such as "Above all else, show the data". He laid out his own definition of the term visualization; it’s the projection of data for some purpose and some audience. There was a quick demonstration of some of the ‘hardware’ that people possess for image processing that visualizations can take advantage of. A quick display of two slides, containing a scattering of identical squares, but one with a single small circle in place of a square, shows how quickly our brains can spot some differences using pre-attentive visual processing.

A good question to ask before embarking on a visualization is whether a plain text list will accomplish the same job, since that can be both a lot simpler to create, and easier to understand if you just need to order your data in a single dimension. As a demonstration, he showed a comparison of a table listing the ordering of 9/11 terrorists in their social network based on four different ranking measures, such as closeness, and then presented a graph that made things a lot cleared.

He has prepared a formal model for the visualization process, with the following stages:

- Phenomenon. Something that’s happening in the real world, which for our purposes includes out on the internet.

- Acquisition. The use of some sensor to capture data about that activity.

- Model/Storage. Placing that data in some accessible structure.

- Preparation. Selection and organization of the data into some form.

- Rendering. Taking that data, and displaying it in a visual way.

- Interaction. The adjustment and exploration of different render settings, and easy other changes that can be made to view the data differently.

There’s actually a cycle between the last three stages, where you refine and explore the possible visualizations by going back to the preparation to draw out more information from the data after you’ve done a round of understanding more about it by rendering. You’re iteratively asking questions of the data, and hoping to get interesting answers, and the iteration’s goal is finding the right questions to ask your data.

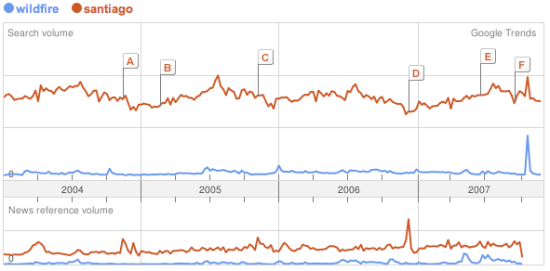

Web 2.0 makes visualizations a lot easier, since it’s a lot more dynamic than the static html that typified 1.0, but why is it so important? Swivel preview is a great example of what can be done once you’ve got data and visualizations out in front of a lot of eyes, as a social experience. The key separation that’s starting to happen is the distinction between algorithmic inference, where the underlying systems make decisions about importance and relationships of data to boil it down into a simple form, and visual inference, where more information is exposed to the user and they do more mental processing on it themselves. (This reminded me of one of the themes I think is crucial in search, the separation of the underlying index data and the presentation of it through the UI. I wish that we could see more innovative search UIs than the DOS-style text list of results in page-rank order, but I think Google is doing a good job of fetching the underlying data. What’s blocking innovation at the moment is that in order to try a new UI, you have to also try to catch up with Google’s massive head-start in indexing. That’s why I tried to reuse Google’s indexing with a different UI through Google Hot Keys.)

One question that came up was why search is so linear? Matt believes this can be laid squarely at the door of advertising, there’s a very strong incentive for search engines to keep people looking through the ads.