I'm doing a short talk at SXSW tomorrow, as part of a panel on Creating the Internet of Entities. Preparing is tough because don't I believe it's possible, and even if it was I wouldn't like it. Opposing better semantic tagging feels like hating on Girl Scout cookies, but I've realized that I like an internet full of messy, redundant, ambiguous data.

The stated goal of an Internet of Entities is a web where "real-world people, places, and things can be referenced unambiguously". We already have that. Most pages give enough context and attributes for a person to figure out which real world entity it's talking about. What the definition is trying to get at is a reference that a machine can understand.

The implicit goal of this and similar initiatives like Stephen Wolfram's .data proposal is to make a web that's more computable. Right now, the pages that make up the web are a soup of human-readable text, a long way from the structured numbers and canonical identifiers that programs need to calculate with. I often feel frustrated as I try to divine answers from chaotic, unstructured text, but I've also learned to appreciate the advantages of the current state of things.

Producers should focus on producing

The web is written for humans to read, and anything that requires the writers to stop and add extra tagging will reduce how much content they create. The original idea of the Semantic Web was that we'd somehow persuade the people who create websites to add invisible structure, but we had no way to motivate them to do it. I've given up on that idea. If we as developers want to create something, we should do the work of dealing with whatever form they've published their information in, and not expect them to jump through hoops for our benefit.

I also don't trust what creators tell me when they give me tags. Even if they're honest, there's no feedback for whether they've picked the right entity code or not. The only ways I've seen anything like this work are social bookmarking services like the late, lamented Delicio.us, or more modern approaches like Mendeley, where picking the right category tag gives the user something useful in return, so they have an incentive both to take the action and to do it right.

Ambiguity is preserved

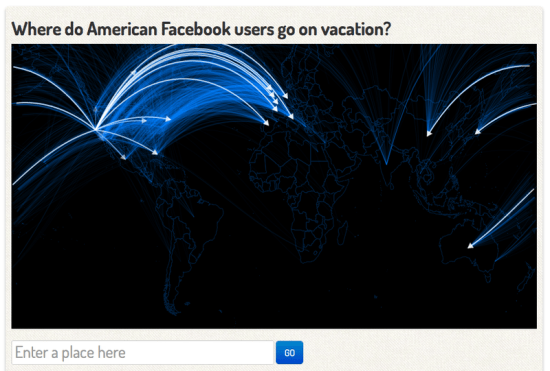

The example I'm using in my talk is the location field on a Twitter profile. It's free-form text, and it's been my nemesis for years. I often want to plot users by location on a map, and that has meant taking those arbitrary strings and trying to figure out what they actually mean. By contrast, Facebook forces users to pick from a whitelist of city names, so there's only a small number of exact strings to deal with, and they even handily supply coordinates for each.

You'd think I'd be much happier with this approach, but actually it has made the data a lot less useful. Twitter users will often get creative, putting in neighborhood, region, or even names, and those let me answer a lot of questions that Facebook's more strait-laced places can't. Neighborhoods are a fascinating example. There's no standard for their boundaries or names, they're a true folksonomy. My San Francisco apartment has been described as being in the Lower Haight, Duboce Triangle, or Upper Castro, depending on who you ask, and the Twitter location field gives me insights into the natural voting process that drives this sort of naming.

There's many other examples I could use of how powerful free-form text is, like the prevalance of "bicoastal" and "flyover countries" as descriptions changes over time, but the key point is that they're only possible because ambiguous descriptions are allowed. A strict reference scheme like Facebook's makes those applications impossible.

Redundancy is powerful

When we're describing something to someone else, we'll always give a lot more information than is strictly needed. Most postal addresses could be expressed as just a long zip code and a house number, but when we're mailing letters we include street, city and state names. When we're talking about someone, we'll say something like "John Phillips, the lawyer friend of Val's, with the green hair, lives in the Tenderloin", when half that information would be enough to uniquely identify the person we mean.

We do this because we're communicating with unreliable receivers, we don't know what will get lost in transmission as the postie drops your envelope in a puddle, or exactly what information will ring a bell as you're describing someone. All that extra information is manna from heaven for someone doing information processing though. For example I've been experimenting with a completely free map of zip code boundaries, based on the fact that I can find latitude/longitude coordinates for most postal addresses using just the street number, name, and city, which gives me a cluster of points for each zip. The same approach works for extra terms used to in conjunction with people or places – there must be a high correlation between the phrases "dashingly handsome man about town" and "Pete Warden" on pages around the web. I'm practically certain. Probably.

Canonical schemes are very brittle in response to errors. If you pick the wrong code for a person or place, it's very hard to recover. Natural language descriptions are much harder for computers to deal with, but they not only are far more error-resistant, the redundant information they include often has powerful applications. The only reason Jetpac can pick good travel photos from your friends is that the 'junk' words used in the captions turned out to be strong predictors of picture quality.

Fighting the good fight

I'm looking forward to the panel tomorrow, because all of the participants are doing work I find fascinating and useful. Despite everything I've said, we do desperately need better standards for identifying entities, and I'm going to do what I can to help. I just see this as a problem we need to tackle more with engineering than evangelism. I think our energy is best spent on building smarter algorithms to handle a fallen world, and designing interchange formats for the data we do salvage from the chaos.

The web is literature; sprawling, ambiguous, contradictory, and weird. Let's preserve those as virtues, and write better code to cope with the resulting mess.