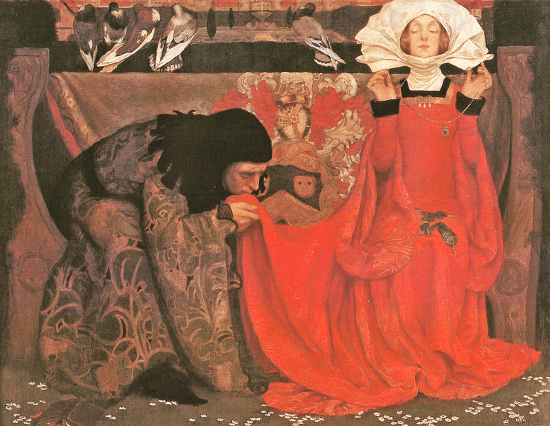

Picture by Sofi

When I saw Cate Huston’s latest post, this part leapt out at me:

‘There’s often a general disdain for front-end work amongst “engineers”. In a cynical mood, I might say this is because they don’t have the patience to do it, so they denigrate it as unimportant.’

It’s something that’s been on my mind since I became responsible for managing younger engineers, and helping them think about their careers. It’s been depressing to see how they perceive frontend development as low status, as opposed to ‘real programming’ on crazy algorithms deep in the back end. In reality, becoming a good frontend developer is a vital step to becoming a senior engineer, even if you end up in a backend-focused role. Here’s why.

You learn to deal with real requirements

The number one reason I got when I dug into juniors’ resistance to frontend work was that the requirements were messy and constantly changing. All the heroic sagas of the programming world are about elegant systems built from a components with minimal individual requirements, like classic Unix tools. The reality is that any system that actually gets used by humans, even Unix, has its elegance corrupted to deal with our crazy and contradictory needs. The trick is to fight that losing battle as gracefully as you can. Frontend work is the boss level in coping with those pressures and will teach you how to engineer around them. Then, when you’re inevitably faced with similar problems in other areas, you’ll be able to handle them with ease.

You learn to work with people

In most other programming roles you get to sit behind a curtain like the Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz whilst supplicants come to you begging for help. They don’t understand what you’re doing back there, so they have to accept whatever you tell them about the constraints and results you can produce. Quite frankly it’s an open invitation to be a jerk, and a lot of engineers RSVP!

Frontend work is all about the visible results, and you’re accountable at a detailed level to a whole bunch of different people, from designers to marketing, even the business folks are going to be making requests and suggestions. You have nothing to hide behind, it’s hard to wiggle out of work by throwing up a smokescreen of jargon when it’s just changing the appearance or basic functionality of a page. You’re suddenly just another member of a team working on a problem, not a gatekeeper, and the power relationship is very different. This can be a nasty shock at first, but it’s good for the soul, and will give you vital skills that will stand you in good stead.

A lot of programmers who’ve only worked on backend problems find their careers limited because nobody wants to work with them. Sure, you’ll be well paid if you have technical skills that are valuable, but you’ll be treated like a troll that’s kept firmly under a bridge, for fear you’ll scare other employees. Being successful in frontend work means that you’ve learned to play well with others, to listen to them, and communicate your own needs effectively, which opens the door to a lot of interesting work you’d never get otherwise. As a bonus, you’re also going to become a better human being and have more fun!

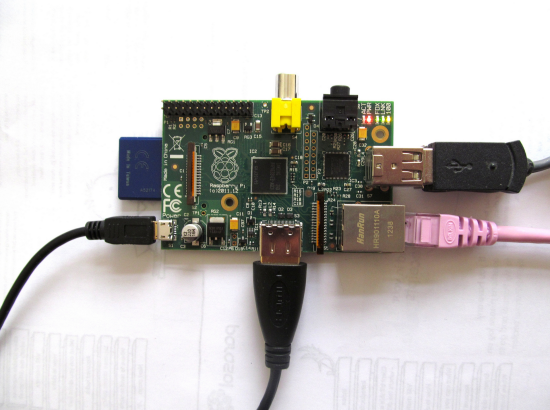

You’ll be able to build a complete product

There are a lot of reasons why being full-stack is useful, but one of my favorites is that you can prototype a fully-working side-project on your own. Maybe that algorithm you’ve been working on really is groundbreaking, but unless you can build it into a demo that other people can easily see and understand, the odds are high it will just languish in obscurity. Being able to quickly pull together an app that doesn’t make the viewer’s eyes bleed is a superpower that will make everything else you do easier. Plus, it’s so satisfying to take an idea all the way from a notepad to a screen, all by yourself.

You’ll understand how to integrate with different systems

One of the classic illusions of engineers early in their career is that they’ll spend most of their time coding. In reality, writing new code is only a fraction of our job, most of the time will go into debugging, or getting different code libraries to work together. The frontend is the point at which you have to pull together all of the other modules that make up your application. That requires a wide range of skills, not the least of which is investigating problems and assigning blame! It’s the best bootcamp I can imagine in working with other people’s code, which is another superpower for any developer. Even if you only end up working as a solo developer on embedded systems, there’s always going to be an OS kernel and drivers you rely on.

Frontend is harder than backend

The Donald Knuth world of algorithms looks a lot like physics, or maths, and those are the fields most engineers think of as the hardest and hence the most prestigious. Just like we’ve discovered in AI though, the hard problems are easy, and the easy problems are hard. If you haven’t already, find a way to get some frontend experience, it will pay off handsomely. You’ll also have a lot more sympathy for all the folks on your team who are working on the user experience!