I’m a firm believer in studying the techniques developed over centuries by librarians and other traditional information workers. One of the most misunderstood and underrated processes is indexing a book. Anybody who’s spent time trying to extract information from a reference book knows that a good index is crucial, but it’s not obvious the work that goes into creating one.

I’m very interested in that process, since a lot of my content analysis work, and search in general, can be looked at as trying to generate a useful index with no human intervention. That makes professional indexers views on automatic indexing software very relevant. Understandably they’re a little defensive, since most people don’t appreciate the skill it takes to create an index and being compared to software is never fun, but their critiques of automated analysis apply more generally to all automated keyword and search tools.

- Flat. There’s no grouping of concepts into categories and subheadings.

- Missing concepts. Only words that are mentioned in the text are included, there’s no reading between the lines to spot ideas that are implicit.

- Lacking priorities. Software can’t tell which words are important, and which are incidental.

- No anticipation. A good index focuses on the terms that a reader is likely to search for. Software has no way of telling this (though my work on extracting common search terms that lead to a page does provide some of this information).

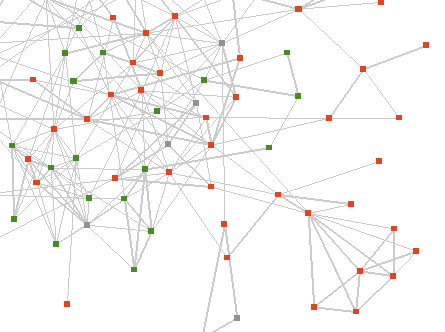

- Can’t link. Cross-referencing related ideas makes the navigation of an index much easier, but this requires semantic knowledge.

- Duplication. Again, spotting which words are synonyms requires linguistic analysis, and isn’t handled well by software. This leads to confusing double entries for keywords.