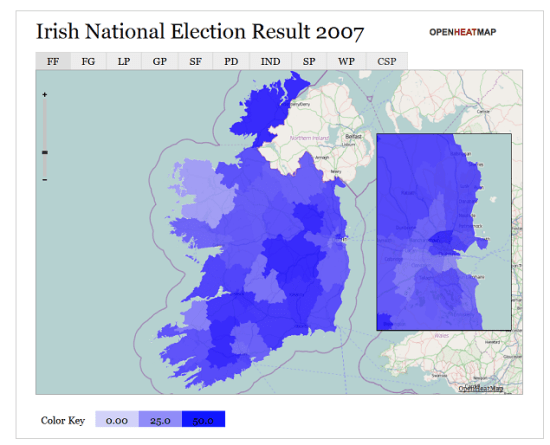

One of my big takeaways from the Strata pre-conference meetup was the lack of standard tools (beyond grep and awk) for data scientists. With OpenHeatMap I often need to pull location information from natural-language text, so I decided to pull together a releasable version of the code I use for this. Behold, geodict!

It's a GPL-ed Python library and app that takes in a stream of text and outputs information about any locations it finds. Here's the command-line tool in action:

./geodict.py < testinput.txt

That should produce something like this:

Spain

Italy

Bulgaria

New Zealand

Barcelona, Spain

Wellington New Zealand

Alabama

Wisconsin

For more detailed information, including the lat/lon positions of each place it finds, you can specify JSON or CSV output instead of just the names, eg

./geodict.py -f csv < testinput.txt

location,type,lat,lon

Spain,country,40.0,-4.0

Italy,country,42.8333,12.8333

Bulgaria,country,43.0,25.0

New Zealand,country,-41.0,174.0

"Barcelona, Spain",city,41.3833,2.18333

Wellington New Zealand,city,-41.3,174.783

Alabama,region,32.799,-86.8073

Wisconsin,region,44.2563,-89.6385

For more of a real-world test, try feeding in the front page of the New York Times:

curl -L "http://newyorktimes.com/" | ./geodict.py

Georgia

Brazil

United States

Iraq

China

Brazil

Pakistan

Afghanistan

Erlanger, Ky

Japan

China

India

India

Ecuador

Ireland

Washington

Iraq

Guatemala

The tool just treats its input as plain text, so in production you'd want to use something like beautiful soup to strip the tags out of the HTML, but even with messy input like that it works reasonably well. You will need to do a bit of setup before you run it, primarily running populate_database.py to load information on over 2 million locations into your MySQL server.

There are some alternative technologies out there like Yahoo's Placemaker API or general semantic APIs like OpenCalais, Zemanta or Alchemy, but I've found nothing open-source. This is important to me on a very practical level because I can often get far better results if I tweak the algorithms to known characteristics of my input files. For example if I'm analyzing a blog which often mentions newspapers then I want to ignore anything that looks like "New York Times" or "Washington Post", they're not meaningful locations. Placemaker will return a generous helping of locations based on those sort of mentions, adding a lot of noise to my results, but with geodict I can filter them out with some simple code changes.

Happily MaxMind made a rich collection of location information freely available, so I was able to combine that with some data I'd gathered myself on countries and US states to make a simple-minded but effective geo-parser for English-language text. I'm looking forward to improving it with more data and recognized types of locations, but also to seeing what you can do with it, so let me know if you do get some use out of it too!